|

|

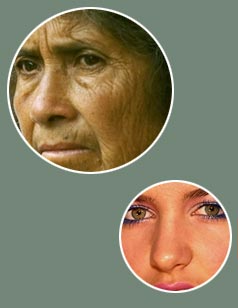

Roma, gypsies and travelling people in England |

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

Gypsies, canal workers, fairground families, circus people and travelling showmen Oxford has a long tradition of holding fairs. One of the earliest, St Frideswide Fair, was held from at least the late 11th century, originally in July, later in October. It was principally a cloth fair, understandably since Oxford was a cloth-making town in the Middle Ages. It was attended by merchants and visitors from outside Oxfordshire; a Bedfordshire draper is recorded in 1420, and a Coventry man in 1423. In the 16th century, the fair passed first to the King, then to the city, but was in decline; it survived in attenuated form until the mid 19th century. The Austin Fair, granted by Edward I for all kinds of merchandise, was held in May and attended by merchants from as far afield as Leicestershire and London. By the late 16th century, this too was in decline. In 1601, Oxford's new charter granted three new fairs in May, June and October. The University objected, fearing a threat to its control of the market. Nevertheless in the late 18th and 19th centuries, a fair was held on 3rd May in Gloucester Green, dealing in toys and small wares. In 1890 it became a funfair, and this continued until 1915. A similar fair was held in St Clement's on the Thursday before Michaelmas. In the early 18th century, it was intended for the hiring of servants, but in 1783 and 1834 it was described as a toy fair, and it survived until the 1930s. St Giles Fair evolved in the second half of the 18th century, from St Giles Feast as it had been known in 1624. In the 1780s it was a toy fair, by the beginning of the 19th century had become a general fair for children, and by the 1830s booths and side-shows catered for adults. It provided opportunities to buy clothes, crockery, baskets and tools, and ‘cheap Jacks', colourful itinerant hawkers, attracted much custom, and by travelling the roads provided a useful service selling goods to working-class and lower-middle class people who would otherwise have been unable to obtain them. St Giles Fair is still an annual event, held early in September. Whether the purpose of fairs was the sale of produce and livestock or the hiring of agricultural or domestic workers, there were always side-shows and amusements. In the 2nd half of the 19th century these included waxworks, freak shows, games of chance and skill, roundabouts, helter-skelter and swing-boats. Late in the 19th century came the ‘galloper' carousels. The early 20th century saw the arrival of the ‘Bioscope', a travelling cinema with an ornate façade and organ, behind which was a seating area. Both showmen and gypsies try to distance themselves from each other, but in fact they share the same fairground fields and the practical problems of the travelling life. Fairground paintwork and gypsy wagon decoration also share something of the same ancestry, although a recognisable gypsy art developed, as did another type of travelling folk art, that of the narrow boats. From the late 17th century the River Thames was becoming increasingly active with bargemen (the earliest Thames bargeman of whom we know was Thomas West of Wallingford in the mid 16th century). In October 1768 a meeting was held in Banbury to discuss the possibility of building a new canal to link the Midlands coalfields with Banbury and Oxford, thereby giving access to London and the Thames. James Brindley, perhaps the most famous of all canal engineers, was appoinated Engineer and General Surveyor. He died in 1772 and his assistant Samuel Simcock, aided by Robert Whitworth, replaced him. In 1769 the Oxford Canal, running from Longford near Coventry, was authorised, and at the beginning of the 1790s the first narrow boats arrived in Oxford. In the same year the connection was made to the Trent and Mersey in the north. More canals were built at the beginning of the 19th century, providing a network of waterways over southern England, giving many villagers their first contact with the outside world. The main cargo was coal, the price of which was now considerably reduced, and heavy goods like road stone, lime, tar and cement. The canal also brought new industrial architecture to Oxfordshire: humpbacked wagon bridges of brick and stone, and wooden drawbridges. Public houses with stabling for canal horses grew up alongside the canal and gained an unsavoury reputation for fighting and drunkenness. From 1844 competition with the railway made life harder and the boatmen began to take their families on board. The decoration of boats with roses, castles and geometric designs now became general. Cabins were filled with crochet work, brass, brown Measham glazed teapots and lace-edged plates, while roses and daisies were painted on water-cans and dippers standing on the cabin roof. The origins of canal art are obscure. Some see a strong Carpathian, central European or eastern European influence. Possibly there is a connection with the gypsies who in the mid 19th century dispersed from Romania to other parts of Europe including Britain. The Oxford Canal is one of the most beautiful in England and now carries an important leisure industry. But there is still a canal community and a high concentration of residential boats. Gypsies are correctly termed Roma, and many speak Romany, an Indo-European language. It is believed that they originated in north-west India. In the first millennium they migrated westwards through the Middle East. They are first mentioned in European written records in the 14th century, and were to be encountered by the 16th century in every part of Europe including England and Scotland. The first wave of groups from India was followed by another, several centuries later in the 2nd half of the 19th century, when gypsies in Romania were freed from slavery and emigrated throughout Europe. They reached American in the early 20th century and in the second half, Australia. But only twenty years after their arrival in Europe they were subject to persecution. Today they must still fight against erosion of their life-style by urban influences and industrialised society. Since the Second World War travel has become more difficult, with numerous rules and regulations making it more difficult to set up camp. Although gypsies have to some degree become assimilated into the cultures in which they live, they still maintain their own identity and customs. The essential feature of their culture is community life, and their distinctive furnishings, decorations and arrangement of belongings. Gypsies traditionally pursued occupations that allowed them to maintain an itinerant lifestyle: metal working and repairs, caning and basket-weaving, music and dance, gathering medicinal herbs, livestock, seasonal agricultural or building work. Today this also includes car mechanics, travelling fairs, circuses and amusement parks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| How to navigate | Project partners | Cultural change | Minority groups |